Exclusive interview: Chamique Holdsclaw talks about her new book, opens up about battling clinical depression and her bond with Pat Summitt

Chamique Holdsclaw’s season-ending injury in 2010 was a devastating blow. The basketball icon’s torn Achilles tendon interrupted her WNBA comeback with the San Antonio Silver Stars and proved to be the worst injury of her career. The sluggishness of the rehabilitation process and a slight re-injury to the tendon caused her to contemplate walking away from basketball altogether.

But sometimes good comes out of bad situations and so it has for Holdsclaw in this case. Over the last year and a half, she expanded her titles to include mental health advocate, speaker, and now, author.

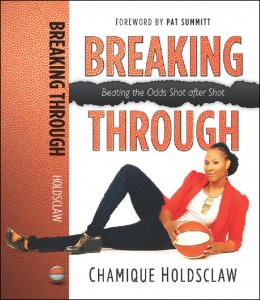

Holdsclaw’s self-penned autobiography, Breaking Through: Beating the Odds Shot After Shot, will be released next month. She hopes that her account of dealing with clinical depression throughout her life and athletic career will help dispel the stigma around the condition, other mental health issues, and serve as hope and inspiration to other sufferers. Holdsclaw not only wrote the book on her own, she is self-publishing it. Tennessee head coach Pat Summitt wrote the book’s forward.

But while Holdsclaw has embraced her new roles with fervor, her return to the WNBA is still uncertain. She said she is waiting to see how she feels physically before deciding whether or not to give it a go this summer.

Even if she does not return, however, the New York City native knows she will be OK as she continues what she calls her journey in conquering depression, which almost six years ago caused her to attempt suicide.

“I realized that my life is more important than basketball,†Holdsclaw said.

Clinical depression has overshadowed Holdsclaw’s life for most of her years, and has consistently interrupted her basketball career since she graduated from the University of Tennessee in 1999, where she won three national championships.

The former WNBA number-one draft pick first spoke about life with depression in a DVD series Words Can Work in 2007. But it has been the public speaking she recently embraced that has proven transformative.

She became a regular speaker for the Morehouse School of Medicine’s NFL Community Huddle “taking a goal line stand for your mind and body†conference series. The panels feature medical professionals, athletes and others who travel throughout the country discussing mental and physical health issues.

Holdsclaw has also become a speaker for the non-profit agency Active Minds, which works to increase mental health awareness on college campuses and acts as a liaison between students and mental health professionals. After speaking at an Active Minds conference this past November in Maryland, other colleges have requested a presentation from the 34-year-old.

She has been taken aback by the response to her telling her story and encouraging sufferers to seek help.

“Athletes come up to me afterwards and doctors,†Holdsclaw said. “A doctor approached me at one conference and told me that what I’d said had really impacted her. I said, ‘me, really?’ I was shocked. I realized, I’m really able to effect lives.â€

Some of the most powerful conversations she has had are with young people who grew up watching her play.

“They’ll say, ‘I watched you, but I didn’t know you were going through anything like this,’†Holdsclaw said. “Other kids will say that they’re experiencing the same thing (depression), and I give them hope. That really inspires me.â€

She said she realized that people “don’t want to hear statistics – they want to hear real life stories.â€

At first, the notoriously private Holdsclaw wrestled with the idea of openly discussing her battle with depression.

“Honestly, at first, talking about it was really difficult – it was really hard,†she said. “It’s a complicated thing that you want to keep to yourself. And for a long time I was stressed about it and didn’t know how to deal with it.â€

“I’m shy – I’m chill and laid back. I’ve always had an inner voice, yet it’s never been one that I wanted to come out. But going on this panel and sharing with so many professionals, high school teams and college athletes – it became like therapy to me.â€

She described writing her new book as therapeutic, as well. Holdsclaw was inspired to embark on the project by motivational speaker Tony Gaskins, who contacted her after she tore her Achilles. Once she got started, the words flowed and she finished the book relatively quickly.

“I had an editor to clean up the punctuation and stuff, but it’s my words – my story, my voice,†Holdsclaw said.

She has also continued to work out regularly for a possible return to WNBA play.

“I’ll see how my body feels,†she said of this season. “It’s all in the body. I don’t want to feel anything again like I’ve felt with this Achilles.â€

Holdsclaw’s newfound willingness to speak and write about her struggle is a radical departure from the way she has traditionally dealt with her depression, which has been to shut down, shut people out and go it alone.

She left her first WNBA team, the Washington Mystics, in 2004 – the midst of her sixth year – as family issues sent her spiraling downward. Teammates said later they had suspected something was wrong when Holdsclaw became uncommunicative.

That fall she finally announced publicly that she was battling depression. After leaving the Mystics, she dropped out of sight. She changed her phone number and did not even return messages from Summitt, who is like a second mother to her.

In 2005 Holdsclaw asked for, and was granted a trade to the Los Angeles Sparks. Five games into the 2007 season she abruptly quit, announcing her retirement from basketball. It came as a surprise to even her close friends on the team.

Holdsclaw said she has always been independent, focused, and never wanted any help. Her grandmother June Holdsclaw, who raised her from age 11, always said her granddaughter was “the least of her worries.â€

But Holdsclaw said she realized after her time with the Sparks that shutting people out is not the answer.

“People were concerned and worried,†she said. “I put some people who care about me through a lot. I realized that when I’m going through some things that I really need to open up to people who are close to me and talk about it.â€

These days, Holdsclaw does just that when she’s having a tough time.

“My close friends are there for me now,†she said. “Like when I have a bad day – because (dealing with depression) is an ongoing thing – somebody will say, ‘let’s go talk about it.’â€

“We’ll go and then I’ll be out of it like that, instead of just going home and thinking about things over and over and over.â€

Holdsclaw’s path to recovery began from what she calls the lowest point in her life: a suicide attempt in July 2006. She had taken some time off during the season to return to New York and help her father, who suffers from schizophrenia. When she returned to Los Angeles, she said she “broke down.â€

Holdsclaw overdosed on prescription medication, but a friend got her to a hospital, where physicians saved her life. After she had stabilized and was lucid, one of the doctors stopped by her room to talk with her. It left a lasting impression.

“The doctor came to me and said, ‘you could have really hurt yourself – death, paralysis, seizures,’†Holdsclaw said. “The doctor says, ‘I don’t follow women’s sports, but I know who Chamique Holdsclaw is, and I’m praying for you. Don’t let this happen again.’â€

She stayed in the hospital for a few days, and then returned to the Sparks to finish the season. None of her teammates knew what had happened.

Consumed with guilt and shame, Holdsclaw said the incident “broke her.†She vowed never to get to such a place of hopelessness and desperation again. And indeed, she’s much stronger now.

In the midst of dealing with her Achilles injury last year, Holdsclaw thought at one point that she would have to retire from basketball, and she worked diligently not to relapse into depression when she could not play.

“It was hard – I really had to focus,†she said. “It’s tough because your whole schedule changes, and you have to figure out where to put your energy and place it. And even though you have other things happening in your life, (basketball has) been something that you’ve loved for so long.â€

But Holdsclaw remained stable and active.

“I can honestly say I did it,†she said. “Because I really don’t want to go back on medication.â€

Holdsclaw’s departure from three of the four pro teams she played for has left some fans puzzled. But perhaps no female ball player has encountered her unique circumstances.

Her parents were both alcoholics. When they could no longer take care of her and her brother Davon, both kids moved in with their grandmother, who lived in housing projects in Astoria, Queens.

Holdsclaw began playing basketball on the courts outside her apartment, and she discovered she had a natural knack for it. She was hooked.

“I would just go with my friends from court to court – I was obsessed with it,†Holdsclaw said. “I got better and better. I stayed out late to play. Then we would take the train to play on West Fourth Street, or go to Brooklyn and battle. That’s just what you do there.â€

At the same time, basketball also became an outlet for a kid who was still upset at having to leave her family home. Holdsclaw attended Al-Anon and Alateen meetings for guidance. But it was not enough.

“Basketball was my coping mechanism for so long,†she said. “That was the way I’d release all my frustration and tension. My grandmother encouraged it, and said ‘you can take out all your frustrations in this house, or on the basketball court.’ So I took it to the court.â€

Her grandmother was the first person to identify the depression. Holdsclaw would not be able to figure it out for herself for many years; she just knew she had negative feelings sometimes that she could not explain.

Holdsclaw adjusted to her grandmother’s ‘passionate and disciplined’ household, and became a model student at Christ the King Regional High School, where she lead the team to four straight state titles. She also became the best female ball player in the city and eventually, the top recruit in the country. That came with a lot of media attention, pressure and expectations.

“I took the fast track in basketball,†she said. “We were doing documentaries in college, had celebrity photographers taking pictures of us all the time.â€

As a result, Holdsclaw said she became a “people pleaser,†striving to meet requests and demands that she did not necessarily want to fulfill. When she was drafted by the Mystics, the pressure on the player many dubbed as “the female Michael Jordan†was suffocating.

“I was always feeling like I was the one person in the room and everybody was looking at me.â€

She said the whirlwind life she lived in high school and college eventually caught up with her in the pros, and the depression she stuffed down with basketball began to surface.

“It was very debilitating – I was low energy,†she said. “It affected my total being mind, body and spirit. I had irrational thoughts, I just wanted to sleep. I just didn’t have the same regard for life that I do now.â€

Another reason Holdsclaw began to unravel when she reached the WNBA was because her safety net – Summitt – was gone. Summitt had been one person she could talk to about her struggles, and it was her coach who set her up with a psychologist while at Tennessee.

“Going to DC I had the same things (fans and support) that I did at Tennessee,†she said. “But I was searching for my Pat Summitt, and Pat Summitt was far gone.â€

She said she left the Mystics because she was embarrassed about her depression, and she felt guilty.

“There’s such a stigma attached to it – I wanted to run,†she said. “I thought, ‘these people hate me.’ I thought that people would be talking about me and my issues, and I wanted a clean start.â€

She regrets that decision now.

“I wish I would have just got through it and not asked for a trade,†Holdsclaw said. “Now I know that I could have just worked through my issues and do the same thing I’m doing now. I didn’t have to leave my home and my friends.â€

Holdsclaw said she left the Sparks because she felt like she was being unreasonably pressured by the management and coaches, and a knee injury she had was being brushed aside. For once, she decided not to be a people pleaser.

She left the Atlanta Dream in 2010 after a dispute with the coaching staff.

Both her grandmother and Summitt always told Holdsclaw to enjoy life and enjoy playing basketball. At last, she is able to do that.

“This whole ride that I’ve had with sports – not until this past year did I really sit back and enjoy everything that’s happened to me.â€

Holdsclaw stepped up for Summitt in December, four months after her mentor announced that she is suffering from early-onset dementia, Alzheimer’s type. Holdsclaw contacted former Vol players, managers and staff and asked them to share written memories of the influence Summitt on their lives, as well as photos. She compiled all 70 entries into a book, had it printed, and presented it to the coach at a luncheon, with many of the contributors present.

“Reading all those letters – it’s amazing how she’s impacted everyone – all these players, and to hear how much they’ve grown from her,†Holdsclaw said. “She’s created this family – this Lady Vol family. It’s a sisterhood.â€

Holdsclaw has remained close to Summitt, and was one of the players the coach called prior to going public with the news of her condition. Holdsclaw said she had been at home working on her book when she got the call.

“I broke down in tears – I just broke down,†Holdsclaw said. “Thirty minutes later reporters are trying to contact me and I’m still crying my eyes out.â€

A few days later, on the weekend, Holdsclaw made the trip to Knoxville to see Summitt.

“I went up that weekend to be with her, just to support her, because she’s always been there for me,†Holdsclaw said.

“I don’t get choked up about much, but you meet a lot of people saying they’re going to do this and they’re going to do that. Since day one, Coach Summitt looked me in the eye and said she’d always be there for me, and she has. She’s an amazing woman.â€

Holdsclaw said that she is part of a Lady Vol club that still hits Summitt up for advice on occasion.

“Making big decisions, like buying housing, or other financial matters – that’s the first thing some of us all do is call Pat,†she said.

When she was going through her darkest times, Holdsclaw said she was worried that she disappointed Summitt.

“Pat had always raised us to be strong and to be strong women, and I wasn’t strong,†Holdsclaw said. “I felt like I’d disappointed her.â€

She eventually realized that was not true. And now Holdsclaw said Summitt’s fight against dementia is what is causing her to consider a WNBA comeback. She had been in the midst of thoughts about retirement when Summitt went public with her condition.

“To see what Coach Summitt is going through now, and with her strength, she’s teaching us again,†Holdsclaw said. “I’m thinking, I’ve got to at least just give it a shot.â€

Whether or not Holdsclaw returns to the court, it will be on her own terms. She is at peace with herself, and as is typical in growing older and wiser, she does not care what others think of her anymore.

“People say whatever they want – I don’t know and I could care less,†Holdsclaw said. “Maybe they say she’s soft or whatever, but I did the best that I could.â€

Holdsclaw’s accolades

- National Champion, 1996, 1997, 1998

- SEC Player of the Year, 1998, 1999

- SEC Rookie of the Year, 1996

- SEC Tournament MVP, 1998, 1999

- SEC Female Athlete of the Year, 1998, 1999

- All-SEC, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999

- Associated Press SEC Player of the Year, 1999

- SEC All-Tournament Team, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999

- US Olympic Team, Gold Medalist, 2000

- Kodak All-America, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999

- Naismith Player of the Century for 1900’s

- Naismith Player of the Year, 1998, 1999

- Naismith All-America Team, 1997, 1998, 1999

- Associated Press Player of the Year, 1998, 1999

- Associated Press All-America Team, 1997, 1998, 1999

- ESPY Award, Female Athlete of the Year, 1999

- ESPY Award, Women’s Basketball Player of the Year, 1998, 1999

- Honda-Broderick Cup, Athlete of the Year, 1998

- Honda Cup Winner, 1997, 1998

- Sports Illustrated Player of the Year, 1998, 1999

- Sullivan Award, 1999

- USA Basketball Player of the Year, 1997

- ESPY Award, Co-Team of the Decade for the 1990’s

- Kodak 25th Anniversary Team

- NCAA 25 Anniversary Team

- NCAA Tournament MVP, 1997, 1998

- NCAA All-Final four Team, 1996, 1997, 1998

- US National Team Member, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000

- Member, Tennessee 3000-Point Club, 3,025 career points

- Member, Tennessee 1000-Rebound Club, 1,295 career rebounds

- Tennessee Record Holder in Career Points, 3,025

- Tennessee Record Holder in Career Rebounds, 1,295

- Tennessee Jersey Retired, 2001

- City of Knoxville named campus street Chamique Holdsclaw Drive, 1999

6 Comments

As a former teammate of Chamique, I really appreciate this article. I have a brother that has been diagnosed with depression as well and people are usually very quiet about the disease. Her book will be an inspiration to lots of people suffering in silence around the world. I'm sure it took a lot of courage to let people into her private life, but it's worth it when so many will be touched.

Amazing article written by an amazing person. Thank you for sharing Chamique!

Thank you Chamique for sharing. Looking forward to the book. Best of luck in your return to the court. See you soon..

Thank u so much for sharing Ms. Holdsclaw. As a young college student suffering from depression and other mental illnesses, I tend to isolate myself from everyone. I hope that in reading your book I can finally learn how to deal with my situation. If it's okay with you, could you take down my e-mail address because I need to talk to someone who can relate to my situation. It's ladyash_18@yahoo.com thanks!

I’ve watched and followed you for years,

I’m so proud of you. And I can relate to your situation, I’m going through it

Thanks for sharing 'Mique~ You are a ture inspiration! I am looking foward to reading your book.

Comments are closed.