Chamique Holdsclaw’s autobiography an engaging read about overcoming clinical depression

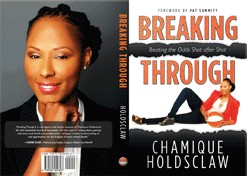

Breaking Through: Beating the Odds Shot After Shot Published by Chamique Holdsclaw, LLC Holdsclaw.com or Amazon.com |

Chamique Holdsclaw wrote her new autobiography in hopes that her account of overcoming clinical depression would inspire other sufferers to seek help and recover, as she has. Her work may fulfill that mission, in part due to the perseverance she shows throughout her life.

But the basketball icon’s book, Breaking Through: Beating The Odds Shot after Shot also embodies a very humanizing message: even when you are a celebrity athlete, tragedies happen, obstacles pop up, and things do not go as planned. It is the universality of the themes in Holdsclaw’s interesting life, and the candidness with which she conveys her story, that makes her self-published work an engaging read.

In the book’s introduction, Holdsclaw chronicles the lowest point in her life – her suicide attempt in 2006. Diagnosed with clinical depression for two years, she saw her recovery go out the window with the illnesses of both her father and stepfather that summer. Being forced to once again be “the strong one” in her family proved to be the breaking point for Holdsclaw, who overdosed on her anti-depressant medication. Because she had called a friend as she was doing so, her life was saved, and since then, she has been committed to recovery.

Foreshadowing events to this incident can be seen throughout Holdsclaw’s life, which she discusses chronologically after the introduction: kicking a garbage can and storming out of practice during high school; pushing people away. Chapter 18, where she discusses her first breakdown, gives the reader an honest look into the dark world of depression.

As the 2004 WNBA season progressed, Holdsclaw had become increasingly withdrawn from others, as well as lethargic. She would wake up in cold sweats, and was metacognitive enough to realize she was having irrational thoughts, but she felt she couldn’t talk to anyone about it.

“I was so deep in a hole I was starting to scare myself,” she wrote.

Alerted by a worker on the property where she lived, a doctor friend finally came to Holdsclaw’s home, and got her to open the door. She found Holdsclaw sitting in the dark, where she’d been for three days without realizing it, having crying bouts. The doctor set Holdsclaw up with a psychiatrist, who prescribed anti-depressants.

Her journey back from her suicide attempt included learning more about depression, regularly reaching out to others, and – ironically – quitting the WNBA for a while. Fans have long been puzzled by the actions of Holdsclaw, once dubbed “the female Michael Jordan,” who seemed to have it all. But through both her disease and her life, Holdsclaw shows that things aren’t necessarily what they seem.

Holdsclaw went to live with her grandmother at age 12, because her parents were alcoholics and couldn’t take care of her and her brother. She initially had trouble adjusting, including cutting classes for a time, before she settled into her grandmother’s home.

Her four state championships at Christ the King Regional High School have been well-documented, but Holdsclaw didn’t even play her freshman year, because there were older and better players in front of her. In the midst of what was to be a glorious senior year, a close relative died.

When Holdsclaw first got to the University of Tennessee to play for Coach Pat Summitt she didn’t think she would make it, either in practices or the classroom. She ended up helping the Vols win a national title and winning the conference rookie of the year honor, but it took another year for Holdsclaw to begin excelling academically. It was only then that she felt she had truly grown up.

Her early years in the WNBA with the Washington Mystics were full of instability, due to the constant changing of coaches. Throughout, the pressure continued on Holdsclaw, who had been hyped since her high school days. Ultimately it proved to be too much to bear, and many times she found herself playing basketball out of obligation rather than love, where it had started.

Through the book, the reader sees that although Holdsclaw was sponsored by Nike, Gatorade and others, she still had yet to face her issues early in her professional career, including dealing with the death of her grandmother. She put on a happy face so well that no one imagined she had any issues – something to which many can relate.

Tennessee Lady Vol fans who have read Summitt’s bestseller Raise the Roof will enjoy the movie effect of Holdsclaw’s memoir in hearing her side of events through winning three national championships. We read Holdsclaw’s version of being kicked out of practice as a freshman, welcoming the other two “Meeks” to campus in her junior year, kissing the floor as she came out of her last home game as a senior, and other events. It is interesting to compare coach and player viewpoints.

Holdsclaw’s life has been eventful, which makes Breaking Through a page-turner. It is also engaging because she writes just like she talks – easygoing and sweet. This is a book every basketball fan should have, because there is so much history in it.

Through telling her story, Holdsclaw personifies and demystifies not only clinical depression, but the life of a celebrity basketball player. She reminds us that we all have issues to face and obstacles to overcome, no matter who we are. The important thing is to face them.